The other week one of my direct reports found a cache of old papers in a file cabinet in the electrical room. Finding papers in a government building is not news. Finding old papers is kind of cool, though. He made up a stack and left them on the table in my office, because he knew I’d be interested, (and because he didn’t know what to do with them).

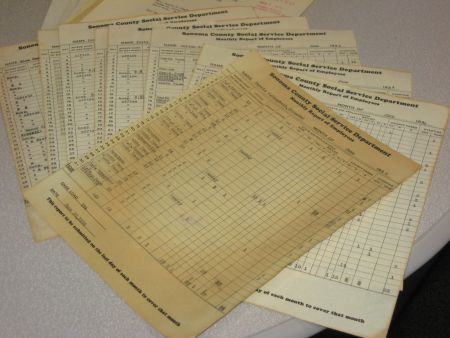

Our building dates to the mid-1960s, and the same department (Social Services, later named Human Services) has been in it the whole time, so it’s not such a shock to find out-dated paperwork. Usually it’s from the 1980s. This stack had material from the 1960s, and even more interesting, from the 1930s.

The oldest work papers dated from 1934. That is more than 70 years ago; before World War II, during the Great Depression; before photocopiers, mainframe computers, fax machines; before the internet, cell phones and American Idol; before an interstate highway system, before parking meters, before television. These papers are carbon-copies, not photocopies. They are the real thing.

*

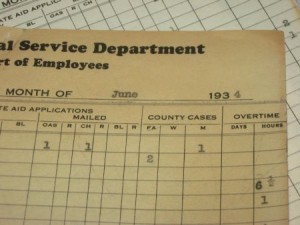

Bessie W Campbell was Director of the Social Services Department in June, 1934. Mrs. Campbell was one of seven employees, according to the Employee Reports from that month. At the end of the month each worker completed a report showing how many field visits they made and how many office interviews they did, by day of the month. “Sunday” is typed in at certain dates, implying strongly that these women (all seven are female) worked on Saturdays.

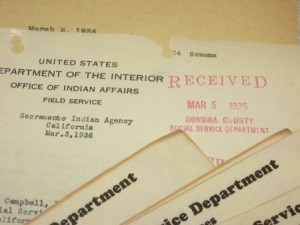

It seems like a lot of their time was spent getting funds for local people on Indian Rancherias, or who had moved off the Rancheria but might still be eligible for federal funds. We see social workers attempting to persuade the federal Office of Indian Affairs to consider the needs of “crippled Indian children,” elderly folks, or families. On March 2, 1936, Bessie Campbell tries to persuade Mr. Roy Nash that an Indian woman named Mary S, who lived on the Geyserville Rancheria for a long period of time but had moved to the town of Windsor to look for work, should qualify to be a ward Indian and be allowed Federal Supplies. On March 3, Mr. Nash replies, “Replying to yours of the 2nd instant, relative to Mary S, this girl has ward status, and it would be satisfactory for you to issue order for necessary aid to be paid by this office.” We know that Mary S was born in the 1890’s and, in 1936, is really no longer a girl.

Federal Supplies were one benefit available to Indians on Rancherias or who qualified for an allotment even though they had moved away. A list provided shows that in calendar year 1935, Sonoma County provided $314 worth of supplies to nine families, including the family of Mary S, above.

Some things never change, and one is the innate bureaucratic desire to squabble over jurisdiction—in other words, to make someone else responsible for something. Among the papers of the 1930s is a carbon copy of a letter from H.H. Shuffleton, the County Auditor of Shasta County to Miley M Pope (Miss), of the Department of Social Welfare in Sacramento, California. The letter was written in March, 1930. In this three page document, Shuffleton lays out a set of questions he posed to the Department of Indian Affairs in order to determine whether a widowed Indian woman, who is “unallotted, but has inherited interests. . .” is eligible for federal services. Each question was answered by the Department, and the result is “No.”

Mr. Shuffleton goes on to say, “ . .as I said at the first of this letter, I saw after the first conference with the Indian Department that we would be “stuck” with the _____ case.” He feels successful, however, because the list of questions gives the counties a ”definite method of determining responsibility for each and every Indian case.” Shuffleton notes gleefully that . . .”Shasta County is coming out considerably to the good as we have unloaded approximately $175 a month on the Indian Department before, so we can afford to take some of them back.”

Sonoma County didn’t have anything to do with the case in question, and Mrs Bessie W Campbell is not cc’d on the letter. Plainly, many copies of this letter were typed and shared with counties, who used it as an informal handbook to determine jurisdiction; much the way that currently, counties share answers we get from our elusive state analysts via e-mail.

Our de facto time capsule gives us an intriguing scrap of day-to-day procedure. I wonder what these seven women were like. I wonder what Bessie was like. I wonder where she lived, what her husband was like (or was she widowed?). I wonder if she drove a car, what church she went to. I wonder what she thought about the job she did, and the people she helped.

Another thing that didn’t change in 70 years? As near as I can tell, the department used exactly the same-shaped date stamp in 1934 as we are using now. For all I know, it’s the exact same stamp.

Hi Marion – loved this post and can’t wait to see more of the real items! What a gem to find after all these years. – Karen

Dear Marion – Here it is 2021 so I’m not sure this will get to you, but in case it does I wanted to let you know that can share a bit more on who Bessie Campbell was. As it happens I’m researching a house she occupied with her husband, Harold Campbell from 1901 (when she got married) to 1919. The house is in Petaluma. Bessie lived to be 108 years old. I hope you get this and can email me.

Katherine, that’s so exciting! I’ll send you an email.