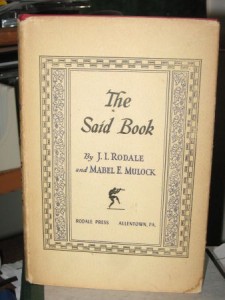

I shelled out $14 (eight for the book, six for shipping) to get my hands on JI Rodale’s evil grimoire, dedicated to the Dark Elder Gods of Bathos—The Said Book.

You may not have heard of JI Rodale, but he has affected your life. His pernicious, seductive words, so honeyed and so venomous, have dripped secretly into your ears while you thought you were sleeping. They have slithered into the hearts and even souls of gifted young writers, like the sentient roots of some dark, evil, eldritch, hell-sprung, twisted, gnarled, evil (did I say evil?) tree, clinging, thriving, driving out the good clean impulses and replacing them with really, really bad things, like adverbs and melodramatic action.

Said? they whisper. Such a bland, boring word. Why not “simper?” Don’t you think he’d “simper?” Just write it down. Nobody will ever know.

Said? How dreary. Can’t she say it with a juicy adverb? Why not “furiously?” Why not “flirtatiously?” Why not “in a fit of glorious rage?” Just write it down. Go ahead. You know you want to.

Yes, in 1947 JI Rodale, with his wicked accomplice Mabel Mulock (actually, I have no idea who Mabel Mulock was, but she shared publishing credit with Modale,) declared war on the straightforward “said expression” as he termed it, and delivered a book full of bad other choices—and, as if a menu straight from hell weren’t enough, a second section of the book loaded with fatty, high-salt, low-nutrient-value adverbs. Why? Well, Mr. Rodale says that he thinks the word “said,” is repetitive and boring.

He slips up on page 16 of my edition, though, and admits his true purpose, when he writes about JP Marquand (and later Hemingway and Steinbeck).

Marquand uses the word “said,” a lot, Rondale notes, “. . . but Marquand can get away with it because his writing has substance. And so it is with the Hemingways and the Steinbecks.” He goes on to say that Hemingway can get away with “said, said, said, said,” because he balanced it out with “hells and damns.”

Marquand’s writing has substance. Yours and mine does not, so we’d better ladle up those alternative words and slap on the adverbs.

After his mock-scientific analysis of some famous writers and choices for “said,” Rodale gives us some choices.

One can Accuse. One can accuse disgustedly, unjustly, deliberately, sternly, vainly.

Or, one can Advocate emphatically, passionately, absurdly, warmly, fanatically, ardently.

One can Expostulate fiercely, petulantly, madly, mildly (expostulate mildly? I don’t think one can.)

One can Implore piteously, beseechingly, plaintively, or in tears.

One can Jabber loquaciously. Why, yes, I suppose one could jabber loquaciously. I might not assume, if you were jabbering at me, that you were loquacious. I might think you’d just had one too many double espressos.

Please note that Rodale does not recommend you use these flashy words just in narrative, as in “She implored the judge for leniency.” No. He wants them used as speech tags. “‘Please, Your Honor, give my brother a second chance,’ she implored piteously.”

I thought this was probably Rodale’s first/only book, even going to far as to assume that, since it was published by Rodale Press, that it was a vanity project, or Daddy helping out an ineffectual son. Rodale has two other books to his credit/blame though; one is a synonym finder called The Sophisticated Synonym Book, and the other is The Substitute for Very. Here’s a thought about how to deal with the word “very.” Don’t use it. Or you can take Rodale’s advice. Here are some suggested substitutions for “very” as a qualifier of “risky:” altogether; notoriously; obviously; admittedly; gravely; seriously; inordinately; peculiarly (my personal favorite); inescapably. Using The Substitute for Very would be inescapably, peculiarly risky.

But The Said Book is his master work in his fiendish plan to destroy new writers. It was bad advice in 1947. It’s bad advice now. We have now all grown up reading alongside movies and TV, and, more importantly, talking and listening to people. We are used to watching body language and facial expressions for clues to motivation and behavior. We are used to paying attention to the rhythm of words and word choices in order to decipher meaning. Like it or not, text has to play by many of those same rules.

I found The Said Book on abebooks.com, and The Red Onion Bookstore shipped it within a week. This is not a reprint. Rodale himself apparently didn’t believe in the timelessness of his work since the book was not printed on low-acid paper and the pages have darkened to the color of toast. The logo of Rodale Press is a capering male figure playing some kind of wind instrument, a trumpet or something, but given Rodale’s dangerous influence I prefer to think of it as a blow-dart tube. By the way, I am delighted with the condition of the book because I conjure up a fantasy of Red Onion Books having an entire wall devoted to the unsold volumes.

I pictured Rodale’s trilogy of terror lined up on the desks of cheeky young guys who wrote the company newsletter, or the dutiful authoresses of The Garden Club’s weekly newspaper column, next to the typewriter, just above the stack of carbon paper, all through the fifties and sixties. Unfortunately, modern writers have still fallen prey to this book’s influence. Most recently, The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack owes a lot to The Said Book, all of it bad.

I have seen the book. I have looked its evil in the face. I have turned its foxed pages to read the horrors its author wants to inflict on us, and I have returned from the caverns of doom to tell you this; friends don’t let friends use The Said Book.

I don’t think it was your intention, but I’m actually curious about the book now! How did you hear about it?

I second your advice about ‘very,’ and ‘just’ and about a thousand other words.

Oh, I think people should look at it, they shouldn’t emulate it! My writers group leader uses the term “said-bookism” a lot. She told us the story but I wasn’t sure there had been a real book. Then I read The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack, and his speech tags were egregious! It inspired me to look up the book, and there it was. You can find it for less than I paid (like a dollar) but the copy I got is just so distressed that it’s precious.

“Here’s a thought about how to deal with the word ‘very.’ Don’t use it.”

Almost every time I have Fred review one of my drafts for Magazine Monday, he finds an errant “very” that slipped in there somehow. I don’t know why this word devils me, but it does. Very often, in fact.

We’re currently reading “Sixkill,” Robert S. Parker’s last Spenser novel, and we’ve both noticed that Parker never uses any word but “said” as a speech tag. Never. It’s very, very interesting. Very.

Terry, I was going to try to our very-ize you. Then I read your comment again and realized what a think of beauty it is. Well-played!

Pingback: Said Posterism | bryn benning

“Yes, in 1947 JI Rodale, with his wicked accomplice Mabel Mulock (actually, I have no idea who Mabel Mulock was, but she shared publishing credit with Modale,)…”

Ah! Back in 2009, I wrote an article on The Said Book, and I can tell you that I learned from the revised 1948 edition that Mabel Mulock was the head of the Allentown, Pennsylvania High School English Department. That may explain a lot…

Ohhh, interesting! Can you link to your article? I’d like to read it.