The best writing workshops give me a model against which I can compare my work. David Corbett’s master class, Character is the Engine of Story, gave me that model and took me back to those basics I tend to forget.

The best writing workshops give me a model against which I can compare my work. David Corbett’s master class, Character is the Engine of Story, gave me that model and took me back to those basics I tend to forget.

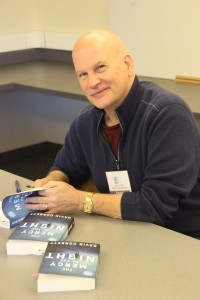

David devoted the first hour of the Thursday workshop to a discussion of character and story. He boiled it down. “What does your main character want? What is the obstacle to achieving it?” Then he added another layer, one that goes to backstory – what does your character yearn for?

This “yearning” is not the same as the thing/outcome the character wants. David used that great Hitchcock term “Maguffin” to address the wanted thing. In the Maltese Falcon, the “black bird” is the Maguffin. The list of compromised agents, the launch codes, the magical sword, the crown; all those are things a character can want. The character can want to get home (Cold Mountain), can want to start/keep a business, want the family home, want to bury a deceased loved one. “Yearning” is deeper; it’s related to the main character’s wound or lack. It is the thing the character images they would have if they led the life they really wanted. Who is the person the character, deep down, wants to be? That helps identify the yearning.

The yearning if often tied to the character’s Weakness/Wound/Limitation/Flaw, for which we used the acronym WWLF. In Corbett’s book The Mercy of the Night, Jacqi wants to earn $2,000 so she can leave town. What she yearns for is a life free of the labels the town has put on her, an attempt to be her own person, without baggage.

Basics, though: What does the character want?

The story I brought to be workshopped had been through many revisions already. It’s a “caper” or a heist story with a scam artist main character. The first two-thirds of the story count on the reader not knowing exactly what was going on under the surface. At the two-thirds point, the “real story” is revealed. From then on the story goes flat.

Part of the reason for the flatness is that I also played, originally, with story structure in this one; and I counted on an unusual structure to provide suspense. It did, in a way, if making the story unreadable counts as “suspense.” When I re-ordered the story, I still had a flat ending. The other problem was that now I had a beginning that was pretty polished and well written. When I reread it, I knew that, vaguely, it stopped being interesting about ten pages from the end, but I pretended that didn’t matter, because I thought I couldn’t fix it.

I forgot to ask what the characters wanted.

There are several secondary characters, but mainly the story focuses on four; a wealthy patriarchal wizard in Prohibition-era Seattle, his magical son, his unmagicked daughter and the young woman he hires as a companion for the daughter. The daughter, Fiona, is about to be married off, and she’s gotten rebellious. What I had forgotten about Fiona, in all my tinkering with the mechanics of the story, was that she was in love with someone else. She is an energetic, rebellious woman in love with a forbidden lover. There is perhaps no greater chaos engine in fiction than that. Why wasn’t I using it?

This meant I had to think about what the brother wanted. In the first go-round, I was a partisan in this fictional family. All my sympathies were with Fiona and I thought the brother was spoiled and obnoxious. I still do, and he still is, but what he wants (to be respected the way his father is) suddenly meant that the last ten pages of the story wouldn’t go so smoothly, not if the brother sees his position threatened. Suddenly I had organic suspense up to the last page.

At least, I hope so.

Back to basics. It does work.