Breathe in. Pay attention to how your chest, your shoulders, your lungs feel. Breathe out. Feel the air move against the sides of your throat, your nostrils.

In your mind, do you separate those two actions, breathing in and breathing out? I usually don’t. It’s all breathing. (If I do consciously separate them, it’s usually a sign I’m in some distress; like I can’t do one of them and I need to.) I don’t say things like, “I came from a family of inhalers, but at school I converted to exhaling because it just makes more sense.”

For some people, in some cultures, there is no divide between science and the sacred; no split between the scientific method or advanced technology and reverence. There is no continuum with “science” at one end and “the sacred” at the other.

I am not one of those people. I want to be.

The HawaiiCon panel “SF, Science and the Sacred took a look at this very debate. SF, they said, is a “safe space” (and they used that term deliberately) in which to play with questions about the ways science and the sacred intersect.

Tim Slater is, in his own words, “An astronomer and a Christian. Depending on what group I’m with, one of those two always elicits surprise.”

Kalah Perkins has a Masters in Divinity and is a non-denominational chaplain who has spent time with monks in Nepal, and at large telescope arrays in several parts of the world. Her primary interest is social justice issues. Like Tim, she said, she is considered “the artistic one with the telescope guys, and the scientific one with my artistic friends.”

Lou Mayo is an astronomer with a specialty in helio-physics, who teaches at Marymount California University. He also reaches aikido and other martial arts.

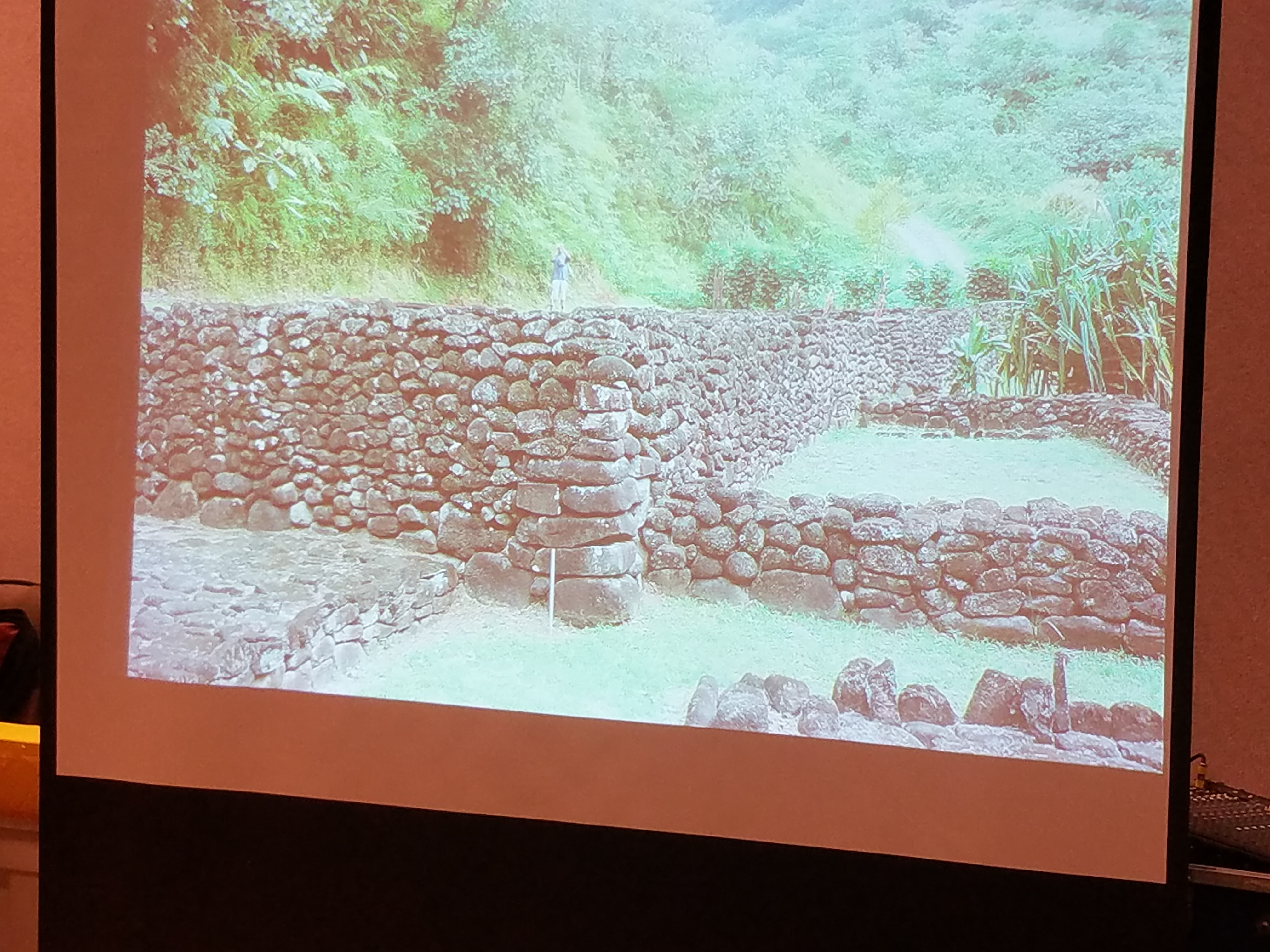

Keao NeSmith is a native Hawaiian who teaches at the University of Hawaii Manoa. He translates works into Hawaiian (he is working on the Harry Potter series now) and is part of a group who restored and maintains a heiau – a sacred ritual platform—on Kauai. I never did get what his degree is in.

This was a wide ranging discussion that set off connections in my head like tiny super-novas. I could have listened to them for another hour—maybe two. I could listen to them now.

Back, though, to this distinction between spiritual and scientific. Slater said that modern geology shows us (in this case literally shows us, because we have underwater photography of the “hot spot”) that the northern part of the Hawaiian Archipelago was formed first, and that the Big Island, the largest island, is in fact the youngest of the chain. Hawaiian cosmology states that the Big Island is the oldest island in the chain. Hawaiians can hold both of these ideas in their heads at the same time. “It’s quite silly to think you can’t understand a thing from both your spirit and your mind.”

Perkins recounted the experience of seeing a distant galaxy through a telescope. A friend said, “Well, where is God in all of this?”

“Where isn’t God in all of this?” Perkins said.

Lou Mayo said, “We’re not comfortable with the unknown. It’s an existential problem. As a race, we are voyagers, explorers, scientists.” He does not see science and faith as in opposition, he said, rather, “At right angles to each other. Science says, ‘show me the money,’ and faith says, ‘I am here.’”

I loved that image even if I don’t quite see how the “graph” of science/faith quite works.

Slater riffed on the “existential problem.” It’s a big universe, he said, and, with a nod to Fermi’s paradox, an advanced civilization would not destroy itself (Assumption One); so where are they all? “Either there is other life in the universe, or we’re alone, we’re it. Either one is equally terrifying.”

It was when Keao started talking about translating that the conversation got trippy. He wanted to translate H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine, but hit a snag right away. He didn’t know which word to use for “time.” Hawaiian has a word for seconds/minutes and an agreed-upon units of measure (clock-time). There is another word for time, and it means longer intervals, like an epoch. That word is “wa” and it also means a rift or a gap. (Amusingly for Doctor Who fans, my Handy Hawaiian Dictionary defines “wa” as “space, in time or place.”)

An audience member asked if he could put the two words together with a hyphen. “We could, but it wouldn’t make any sense,” he said.

Slater piped up, “It would be like saying north-squirrel.”

I completely understood about the clock-time thing, because many of us from the mainland had been saying we were keeping “California time.” This was because we would bound out of bed at 6:00 am according to the clock in our room or the time on our phone. This wasn’t California time. These were California hours. If you normally get up at six-thirty in CA and you want to keep California time, you’d get up at 3:30 am in Hawaii during Daylight Saving Time. We were actually keeping Hawaiian time, reacting to when the sun came up, and when it got dark.

Nothing to do with the sacred? Maybe not, but Keao went on to talk about the idea of “history.” Hawaiians have a word, mo’olelo, which comes close to meaning, “what we’ve done before.” This can be in the sense of tradition, but, if I understood it right, can also mean something like a “what-the-folks-and-I-did-last-summer” kind of thing. It does not mean an abstract, textbook list of dates and events, a knotted string that starts from things only a bunch of people in parts of Europe a long time ago would be interested in. So, Hawaiians don’t care much about the past, I guess, then, right? Well, no, because “what they have done before” is introduce themselves to strangers, via chant, by providing a list of their family and ancestors. Hawaiians don’t experience what happened before as a knotted string, it’s more like a net, a web that includes extended family, foster family and ancestors. Native Hawaiians, from birth, are part of something.

To me, a large part of the spiritual experience is a desire to be part of something. Usually, it’s a drive to be part of something beyond our quotidian existence. This can lead to great movements like early Christianity and social justice movements… and great works of art. The same yearning leads some of us into Nazism, corporatism and (maybe I’m reaching here) social media addiction. Does a sense of community that reaches through the gap of time, in some way, meet that need?

If you live in Hawaii, you are in a geologically active part of the world. You cannot ignore the fact that the earth, the ground beneath your feet, is not inert. It is dynamic.

Where is God in all of this?

Where isn’t God in all of this?

Lou Mayo seemed to create a category of “things we just don’t know yet,” and he put God in that category. Or maybe he called that category “God.”

Keoa used the word “akua” and defined it first as “unknown.” A moment later he defined it as “a god.”

The idea of God as the Unanswered Question works fine for me. When I experience God, and I do, it is in moments of awe. It might come from seeing the vastness of distant galaxies, or from studying the Milky Way as I walk on a beach in North Kohala. It might come from watching molten rock the color of the setting sun pouring into the ocean, or seeing colonies of coral under a microscope. It might come from reading that a variety of plant that lives in the tropics blooms all over the world at the same time… even the plants that are in hothouses or botanical gardens thousands of miles from their original environment. It might come when I hear that a 400 year old ti plant on Kauai shares DNA with a plant that lives in a valley on Tahititi, a valley named Pele’s Place. The whys and the hows of those things are unknown to me. God as the Unanswered Question.

But enough about me.

The panel did not spend much time talking about SF as the safe space, the bridge between science and the sacred, other than to say it was, and that stories allow us to explore both. For me, the panel was that bridge. I wanted more, and nearly a week later, I still do.