John and Sunai Chambers are master potters. They live out in the country southwest of town in a small house they’ve remodeled and improved over the years, sheltered by a bay tree, surrounded, in rings, by smaller bays, Douglas fir, and up the hill, eucalyptus. Their studio is across the yard. They have three kilns including a salt kiln and John is justly famous for his salt-glaze work.

John and Sunai Chambers are master potters. They live out in the country southwest of town in a small house they’ve remodeled and improved over the years, sheltered by a bay tree, surrounded, in rings, by smaller bays, Douglas fir, and up the hill, eucalyptus. Their studio is across the yard. They have three kilns including a salt kiln and John is justly famous for his salt-glaze work.

Every year in December they host an open house and on Sunday Sunai holds a tea ceremony for their friends and long-time customers. Sunai is a student of the way of tea. Her tea ceremony is simple and relaxed with a lot of room for questions and discussion. This year was more poignant than most because her mother died last year. One of the things Sunai brought back from Japan was a tea bowl she had taken to her mother, from here, many years ago.

Sunai sees tea ceremony as a circle—you coming back to where you started, kneeling, holding the water vessel, the mizusashi. She sees life, beginnings and endings, in some ways as a circle. Plainly her mother’s off-white tea bowl, smaller than some of the others to fit a small woman’s hand perhaps, with its pebbled salt glaze finish, made a circular journey from Northern California, to Japan, back to California.

Sunai had friends visiting, one of whom teaches tea ceremony, and one of her students, Asako, made tea for us. I didn’t take pictures, although I really wanted to, because I knew it would disrupt the atmosphere. It was hard to let those images go and not reach for my camera—the silvery, glistening stream of water from the bamboo ladle into the heating pot, ribbons of steam swirling out, the motion of Asako’s hand as she rotated the whisk in the tea bowl. Her movements were precise and graceful but I noticed that with the first bowl of tea she made, her hands shook slightly. It must be difficult to perform in front of your teacher.

John makes implements for the entire ceremony; tea bowls, the heating pot, the water vessel, the pot for waste water and the lees, and the ceramic brazier. Originally these burned wood or charcoal but now they have a heating element, like a hot-plate ring, set in the bottom. The other utensils are made of bamboo or cloth:

–dipper or ladle, for bringing water from the vessel into the heating hot

–bamboo whisk that looks the stamen of some robust flower, with a flat, circular base

–tea spoon, long-handled with a tiny, narrow bowl.

There is also a tea caddy—Sunai’s is bright red—and the tea maker wears in the bodice of his or her kimono a cloth to be used to wipe the tea bowls clean.

The mizusashi has a lid, a smooth wooden disk. Asako removed it using a specific process. After setting it on its edge, resting against the vessel, she used the bamboo dipper, balanced perfectly across the mouth of the heating pot, to ladle in water. When the water began to steam, she ladled some out into the first tea bowl, into which she had already sprinkled a spoonful of finely powdered green tea. She replaced the ladle exactly and picked up the whisk, which rests on its broad handle, bristles facing up. All of this is done with reverence and mindfulness. She swept it once or twice around the cup in a motion that you would use to fold beaten egg whites into batter. Then she whisked harder, swirling the water and green powder into a bright green froth.

She placed the whisk, bristles up, on the tatami, bowed low to the first guest (the one on the far right) and offered him the tea bowl.

The first guest has a lot of influence over the tea ceremony. If he or she says the tea is too cool or too warm, or the proportion of tea to water isn’t right, the tea maker must start again. This would be a loss of face for the tea-maker. It seems like that could create some high stakes in a political or social situation where not everyone at the ceremony is your friend. Imagine a scene in a novel in which you are the tea maker and your fiercest political enemy is sitting in the position of first guest.

Not the case here, though. The first guest pronounced the tea very good.

<

To accept the tea, bow to the tea maker. Rest the tea bowl on your left palm and curve the fingers of your right hand around it to secure it. The tea maker turns the bowl so that its most beautiful side faces the guest. Hold the bowl, and feel the glaze, which might be satiny smooth or dimpled and pebbled like a golf ball. Admire the beauty that has been presented to you, and then rotate the bowl slightly on your palm so that you are not drinking from the most beautiful side. The first year I went to tea ceremony, Sunai said that the reason was to share the beauty with the person next to you. This year, she gave a longer, less coherent, and probably deeper explanation about showing respect for the elegance and beauty of a utilitarian object, a simple tea bowl. That wasn't quite it either. I realized later that it is about humility.

The bowl is warm, not hot. The top of the tea is a bright basil-green froth. It smells briny, a little like the ocean, and the taste is grassy and bitter—very, very bitter. To balance the bitterness, which I found refreshing, Sunai provided azuki bean cake. The purple rectangles felt smooth to the touch, slightly glossy, about the texture of fudge. Sweet! Sugary, with a honey-like or brown-sugar taste. Many people ate the cake first and then had the tea to cut the sweetness.

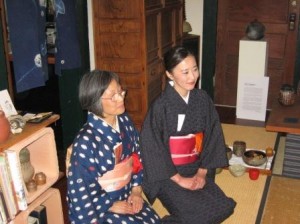

Asako's dark blue kimono had fine, detailed embroidery that looked like a circuit board diagram. As each guest returned their empty cup to her, she ladled water into the used cup, rinsed it, poured the lees into the waste water bowl and wiped the tea bowl dry with the cloth tucked into her bodice.

Sunai talked to me for a few minutes about her mother, imagining her mother taking a few minutes to whisk a bowl of tea for herself in the small, off-white bowl. She said she gave away many things but kept the tea bowl and her mother's sewing machine. I thought about I had kept my mother's sewing machine for seven years after she died, and I don't sew.

There are many schools of tea ceremony. I don't know what is overarching tradition and what comes from each style, and what it personal preference. For instance, I don't know if the way Sunai and Asako bow, placing their hands on the tatami with fingers pointed toward each other, is general tradition or the specific way they were taught. I noticed that they whisked the tea slightly differently; Sunai so fast her hand nearly blurred, Asako a little more slowly. Years of practice? Personal variation? I don't know.

They had so many people there that they were serving tea in rounds. Between groups, Sunai and Asako let me take their pictures.

My friend and I looked around the indoor pottery studio, visited with the other people, and then made our way outside into the cold, moist bay-scented air, to head home.

<

To accept the tea, bow to the tea maker. Rest the tea bowl on your left palm and curve the fingers of your right hand around it to secure it. The tea maker turns the bowl so that its most beautiful side faces the guest. Hold the bowl, and feel the glaze, which might be satiny smooth or dimpled and pebbled like a golf ball. Admire the beauty that has been presented to you, and then rotate the bowl slightly on your palm so that you are not drinking from the most beautiful side. The first year I went to tea ceremony, Sunai said that the reason was to share the beauty with the person next to you. This year, she gave a longer, less coherent, and probably deeper explanation about showing respect for the elegance and beauty of a utilitarian object, a simple tea bowl. That wasn't quite it either. I realized later that it is about humility.

The bowl is warm, not hot. The top of the tea is a bright basil-green froth. It smells briny, a little like the ocean, and the taste is grassy and bitter—very, very bitter. To balance the bitterness, which I found refreshing, Sunai provided azuki bean cake. The purple rectangles felt smooth to the touch, slightly glossy, about the texture of fudge. Sweet! Sugary, with a honey-like or brown-sugar taste. Many people ate the cake first and then had the tea to cut the sweetness.

Asako's dark blue kimono had fine, detailed embroidery that looked like a circuit board diagram. As each guest returned their empty cup to her, she ladled water into the used cup, rinsed it, poured the lees into the waste water bowl and wiped the tea bowl dry with the cloth tucked into her bodice.

Sunai talked to me for a few minutes about her mother, imagining her mother taking a few minutes to whisk a bowl of tea for herself in the small, off-white bowl. She said she gave away many things but kept the tea bowl and her mother's sewing machine. I thought about I had kept my mother's sewing machine for seven years after she died, and I don't sew.

There are many schools of tea ceremony. I don't know what is overarching tradition and what comes from each style, and what it personal preference. For instance, I don't know if the way Sunai and Asako bow, placing their hands on the tatami with fingers pointed toward each other, is general tradition or the specific way they were taught. I noticed that they whisked the tea slightly differently; Sunai so fast her hand nearly blurred, Asako a little more slowly. Years of practice? Personal variation? I don't know.

They had so many people there that they were serving tea in rounds. Between groups, Sunai and Asako let me take their pictures.

My friend and I looked around the indoor pottery studio, visited with the other people, and then made our way outside into the cold, moist bay-scented air, to head home.

hello I actually like this post. Gotta love the Tea, specially oolong Tea.

This is apparently another fake messsage, but I’m leaving it up because the website is a news aggregator, looks pretty neat, and has some information about tea.

Thanks for share this,nice post

Pingback: Art Trails 2010 | Deeds & Words